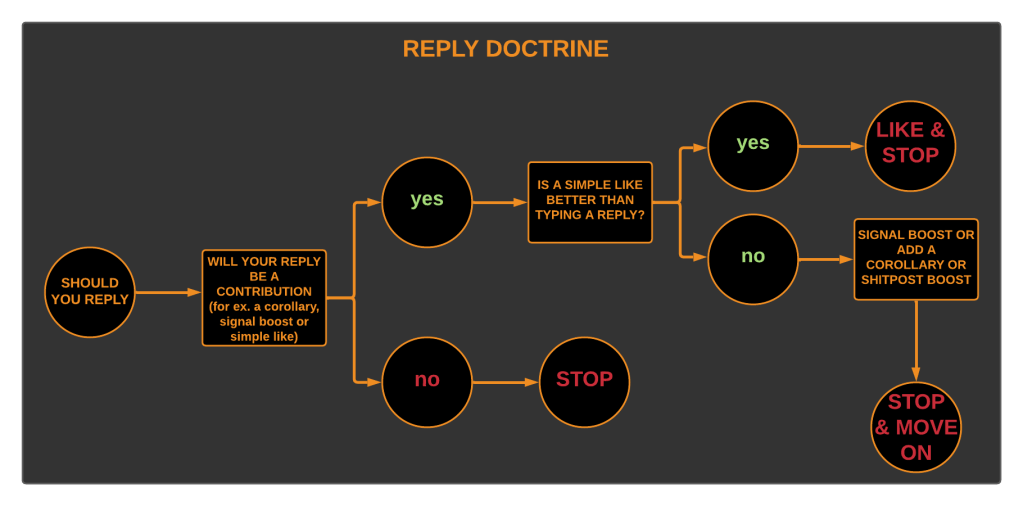

I created the flowchart shown above a few years ago, while still an active Twitter user.

The purpose, was to illustrate the doctrine I applied to my social media usage to share with others as, hopefully, an aid and spark for thought.

Social media has always been terrible and has always been a field of struggle, indeed, war.

How could it be otherwise? The world we live in, a capitalist tyranny, built on mass death, has produced terrible human beings whose inhumanity is on display via electronic networks. It’s a big world and far from everyone is a monster but hard questions must be asked about a global society that openly supports and conducts genocide (shown on social media), violently suppressing dissent against mass murder.

Since October of 2023, when the genocide of Palestinians accelerated, it became clear to many of us that we were in the midst of a global war, waged by elites against all of us to reverse whatever gains had been made in the post World War Two period. In a time of war, our social media usage should become more deliberate, more disciplined and less open about our plans.

On Strategy

There are several books on war that are considered classics. The most venerable is Sun Tzu’s 5th century treatise, ‘Art of War’. In the 1980s and 90s, business idiots, inspired by the Gordon Gecko character in the 1987 film, Wall Street, imagining themselves to be generals (rather than coke addled thieves) flocked to the business section of bookstores to buy, and, mostly misunderstand the text.

Here is an excerpt from the chapter titled ‘Tactical Dispositions’ from the 1910, Lionel Giles translation:

1. Sun Tzŭ said: The good fighters of old first put themselves beyond the possibility of defeat, and then waited for an opportunity of defeating the enemy.

2. To secure ourselves against defeat lies in our own hands, but the opportunity of defeating the enemy is provided by the enemy himself.

4. Hence the saying: One may know how to conquer without being able to do it.

5. Security against defeat implies defensive tactics; ability to defeat the enemy means taking the offensive.

6. Standing on the defensive indicates insufficient strength; attacking, a superabundance of strength.

7. The general who is skilled in defence hides in the most secret recesses of the earth…

[…]

Full at the Project Gutenberg eBook of the Art of War

Today, we lack a “superabundance of strength” and must assume an intelligent, defensive posture.

On social media, this means:

Information Discipline

Resist the urge to overshare. This only provides your enemy with information that can be used against you. Needless to say, activist groups must be especially cautious and only communicate the bare minimum on social media required.

No Study, No Right to Speak

Social media platforms are designed to encourage stupidity, such as: arguing with people you don’t know, will never meet and who may not be people at all (i.e., bots). Conversation on complex topics is not possible with people who are unfamiliar with the topic. When people respond to a post about an article, book, etc with objections based on nothing, ignore them. Argumentation is a time waster and sometimes, a psyop.

Treat Social Media as Enemy Territory

There is a difference between paranoia and intelligent movement through hostile terrain. Do not be lulled into thinking you are among friends (though you may have friends on a platform). The platform owners are your enemies and so are many of the people monitoring and responding to your posts.

The World at War

We are in an age of global war. To many of us, relatively comfortable (though increasingly less so as supposedly democratic states use escalating tactics of control, including via algorithmic means, to suppress ever more restless populations) this sounds dramatic and seems counter-intuitive. After all, bills still must be paid, children cared for and kitchens cleaned. Nevertheless, it is true.

It’s time for each of us to put away our illusions and move more intelligently, ideally in cooperation with others. A critical part of this is changing the way we understand, and use social media.