On September 14, 2023, while touring Twitter the way you might survey the ruins of Pompey, I came across a series of posts responding to this statement from the EU Commission account:

Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority…

What attracted critical attention was the use of the phrase, ‘risk of extinction‘ a fear of which, as Dr. Timnit Gebru alerts us (among others, mostly women researchers I can’t help but notice) lies at the heart of what Gebru calls the ´TESCREAL Bundle.’ The acronym, TESCREAL, which brings together the terms Transhumanism, Extropianism, Singularitarianism, Cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism and Longtermism, describes an interlocked and related group of ideologies that have one idea in common: techno-utopianism (with a generous helping of eugenics and racialized ideas of what ‘intelligence’ means mixed in to make everything old new again).

Risk of extinction. It sounds dramatic, doesn’t it? The sort of phrase you hear in a Marvel movie, Robert Downey Jr, as Iron Man stands in front of a green screen and turns to one of his costumed comrades as some yet to be added animated threat approaches and screams about the risk of extinction if the animated thing isn’t stopped. There are, of course, actual existential risks; asteroids come to mind and although climate change is certainly a risk to the lives of billions and the mode of life of the industrial capitalist age upon which we depend, it might not be ‘existential’ strictly speaking (though, that’s most likely a distinction without a difference as the seas consume the most celebrated cities and uncelebrated communities).

The idea that what is called ‘AI’ – which, when all the tech industry’s glittering makeup is removed, is revealed plainly to be software, running on computers, warehoused in data centers – poses a risk of extinction requires a special kind of gullibility, self interest, and, as Dr, Gebru reminds us, supremacist delusions about human intelligence to promote, let alone believe.

***

In the picture posted to X, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, is standing at a podium before the assembled group of commissioners, presumably in the EU Commission building (the Berlaymont) in Brussels, a city I’ve visited quite a few times, regretfully. The building itself and the main hall for commissioners, are large and imposing, conveying, in glass, steel and stone, seriousness. Of course, between the idea and the act there usually falls a long shadow. How serious can this group be, I wondered, about a ‘risk of extinction’ from ‘AI’?

***

To find out, I decided to look at the document referenced and trumpeted in the post, the EU Artificial Intelligence Act. There’s a link to the act in the reference section below. My question was simple: is there a reference to ‘risk of extinction’ in this document? The word, ‘risk’, appears 71 times. It’s used in passages such as the following, from the overview:

The Commission proposes to establish a technology-neutral definition of AI systems in EU law and to lay down a classification for AI systems with different requirements and obligations tailored on a ‘risk-based approach’. Some AI systems presenting ‘unacceptable’ risks would be prohibited. A wide range of ‘high-risk’ AI systems would be authorised, but subject to a set of requirements and obligations to gain access to the EU market.

The emphasis is on a ‘risk based approach’ which seems sensible at first look but there are inevitable problems and objections. Some of the objections come from the corporate sector, claiming, with mind-deadening predictability, that any and all regulation hinders ‘innovation’ a word that is invoked like an incantation only not as intriguing or lyrical. More interesting critiques come from those who see risk (though, notably, not existential) and who agree something must be done but who view the EU’s act as not going far enough or going in the wrong direction.

Here is the listing of high-risk activities and areas for algorithmic systems in the EU Artificial Intelligence Act:

o Biometric identification and categorisation of natural persons

o Management and operation of critical infrastructure

o Education and vocational training

o Employment, worker management and access to self-employment

o Access to and enjoyment of essential private services and public services and benefits

o Law enforcement

o Migration, asylum and border control management

o Administration of justice and democratic processes

Missing from this list is the risk of extinction; which, putting aside the Act’s flaws, makes sense. Including it would have been as out of place in a consideration of real-world harms as adding a concern about time traveling bandits.. And so, now we must wonder, why include the phrase, “risk of extinction” in a social media post?

***

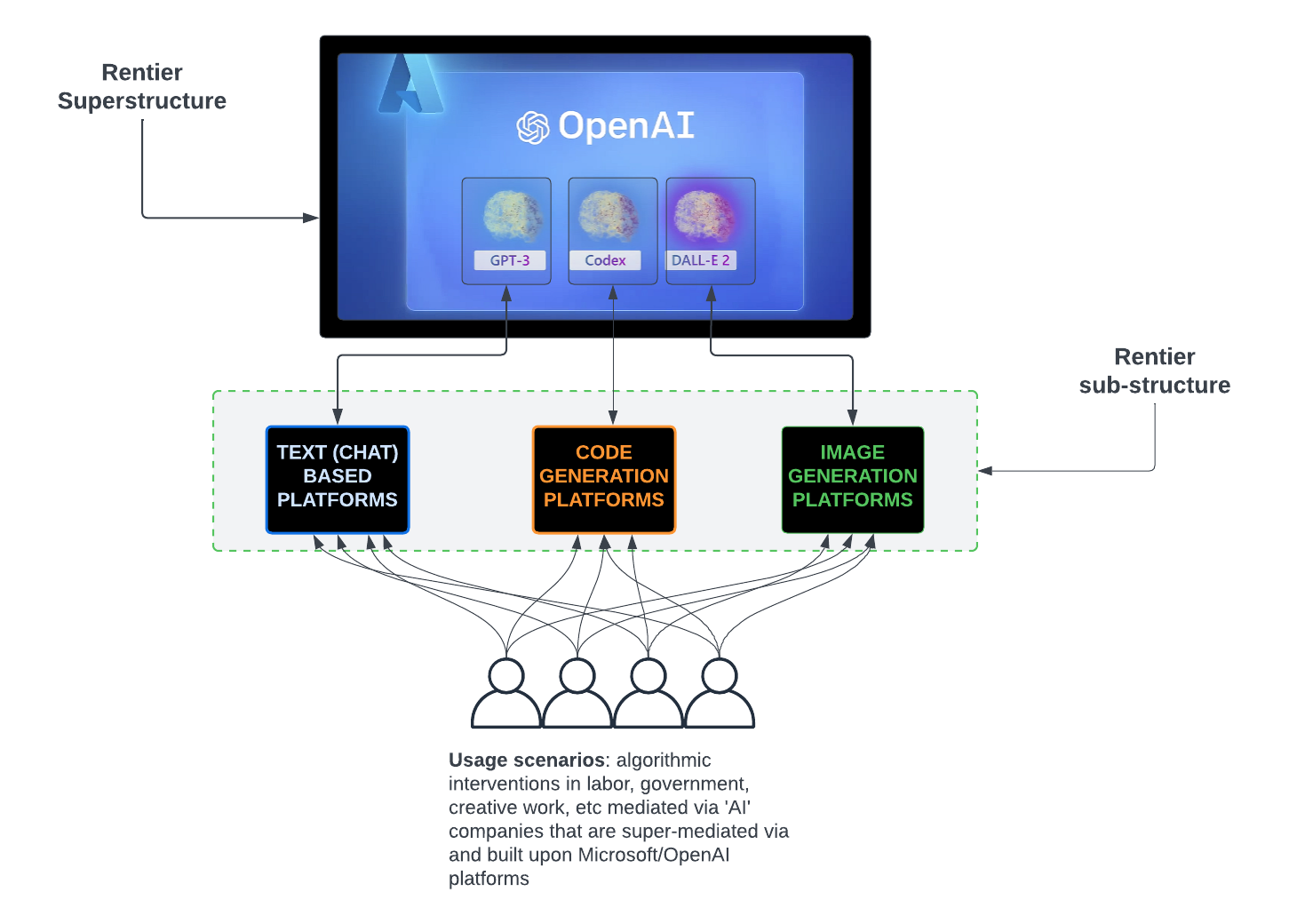

On March 22, 2023, the modestly named Future of Life Institute, an organization initially funded by the bathroom fixture toting Lord of X himself, Musk (a 10 million USD investment in 2015) whose board is as alabaster as the snows of Antarctica once were, kept afloat by donations from other tech besotted wealthies, published an open letter titled, ‘Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter.’ This letter was joined by similarly themed statements from OpenAI (‘Planning for AGI and beyond’) and Microsoft (‘Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4’).

Each of these documents has received strong criticism from people, such as yours truly, and others with more notoriety and for good reason: they promote the idea that the imprecisely defined Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is not only possible, but inevitable. Critiques of this idea – whether based on a detailed analysis of mathematics (‘Reclaiming AI as a theoretical tool for cognitive science’) or of computational limits (The Computational Limits of Deep Learning) have the benefit of being firmly grounded in material reality.

But as Freud might have warned us, we live in a society shaped not only by our understanding of the world as it is but also, in no small part by dreams and fantasies. White supremacists harbor the self congratulating fantasy that any random white person (well, man) is an astounding genius when compared to those not in that club. This notion endures despite innumerable and daily examples to the contrary because it serves the interests of certain individuals and groups to persist in delusion and impose this delusion on the world. The ‘risk of extinction’ fantasy has caught on because it builds on decades of fiction, like the idea of an American Dream and adds spice to an otherwise deadly serious and grounded business: controlling the tech industry’s scope of action. Journalists who ignore the actual harms of algorithmic systems rush to write stories about a ‘risk of extinction’ which is far sexier than talking about the software now called ‘AI’ that is used to deny insurance benefits or determine criminal activity.

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act does not explicitly reference ‘existential risk’ but the social media post using this idea is noteworthy. It shows that lurking in the background, the ideas promoted by the tech industry – by OpenAI and its paymaster Microsoft and innumerable camp followers – have seeped into the thinking of decision makers at the highest levels.

And how could it be otherwise? How flattering to think you’re rescuing the world from Skynet, the fictional, nuclear missile tossing system featured in the ‘Terminator’ franchise, rather than trying, at long last, to actually regulate Google.

***

References

European Union

A European approach to artificial intelligence

EU Artificial Intelligence Act

Critique

Timnit Gebru on Tescreal (YouTube)

The Acronym Behind Our Wildest AI Dreams and Nightmares (on TESCREAL)

The EU still needs to get its AI Act together

Reclaiming AI as a theoretical tool for cognitive science

The Computational Limits of Deep Learning

Boosterism

Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter

Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4