Capitalism, a system as inescapable as breathless news items about Trump, Musk and decay, came into its own during the age of steam power, telegraphs and colonialism (first edition, we’re witnessing the attempted redux), long before the invention of digital computers. The creation of computers, initially, a tool for military purposes (ENIAC, the first programmable digital computer was immediately put to work performing calculations for then still theoretical hydrogen bombs) eventually enabled capitalists, particularly at the commanding heights, to employ what, in military circles is known as command and control at a level of sophistication and intrusiveness previously only dreamed of.

What is command and control?

Consider this excerpt from the essay, ‘Re-conceptualizing Command and Control‘, released in 2002 for the Canadian military and co-authored by Dr. Ross Pigeau and Carol McCann which provides a succinct definition:

“…controlling involves monitoring, carrying out and adjusting processes that have already been developed. Commanding involves creating new structures and processes (i.e., plans, SOPs, etc.), establishing the conditions for initiating and terminating action, and making unanticipated changes to plans. Most acts, including decision making, involve a sophisticated amalgam of both commanding and controlling.”

Everyone who has worked in a corporate enterprise, the land of key performance indicators (or, KPIs) and other metrics gathered and analyzed to determine profit and loss, and even, in some cases, who lives and dies, understands this definition in their bones; it captures the hierarchical structure of business, which is a form of tyranny (some of these fiefdoms have pleasant break-out rooms, decent coffee and declarations of workers being in a family until, of course, restructuring and endless re-orgs casts ‘family members’ onto the street).

From the birth of the corporate era, companies have pursued operational and logistics control to ensure profit, market share and high valuation. So-called scientific management, created and promoted by mechanical engineer and early managerial consultant Frederick Taylor in the late 19th century, was the first dedicated effort of the industrial era. Sears and Roebuck, a 19th century retail and mail order behemoth, the Amazon of the pre-digital computer age, employed an army of people, scientifically managed, to run its vast enterprise. There are commonalities between the Sears of old and Amazon:

The primary difference between Sears in the 19th century and Amazon today is the latter’s use of digital technology to enhance command and control techniques, enhancements that make it possible for Amazon to surveil delivery drivers on their routes, among other outrages.

From Brighter than a Thousand Suns to the Office Commute

Digital computation’s first assignment was performing the subtle calculations physicists such as Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam needed to bring the thermonuclear devices of their fevered dreams to irradiated life. From that beginning, brighter than a thousand suns, the age of command and control fully took shape with the creation of systems such as the US Air Force’s Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) described in a Wikipedia article:

“The Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) was a system of large computers and associated networking equipment that coordinated data from many radar sites and processed it to produce a single unified image of the airspace over a wide area. SAGE directed and controlled the NORAD response to a possible Soviet air attack, operating in this role from the late 1950s into the 1980s.”

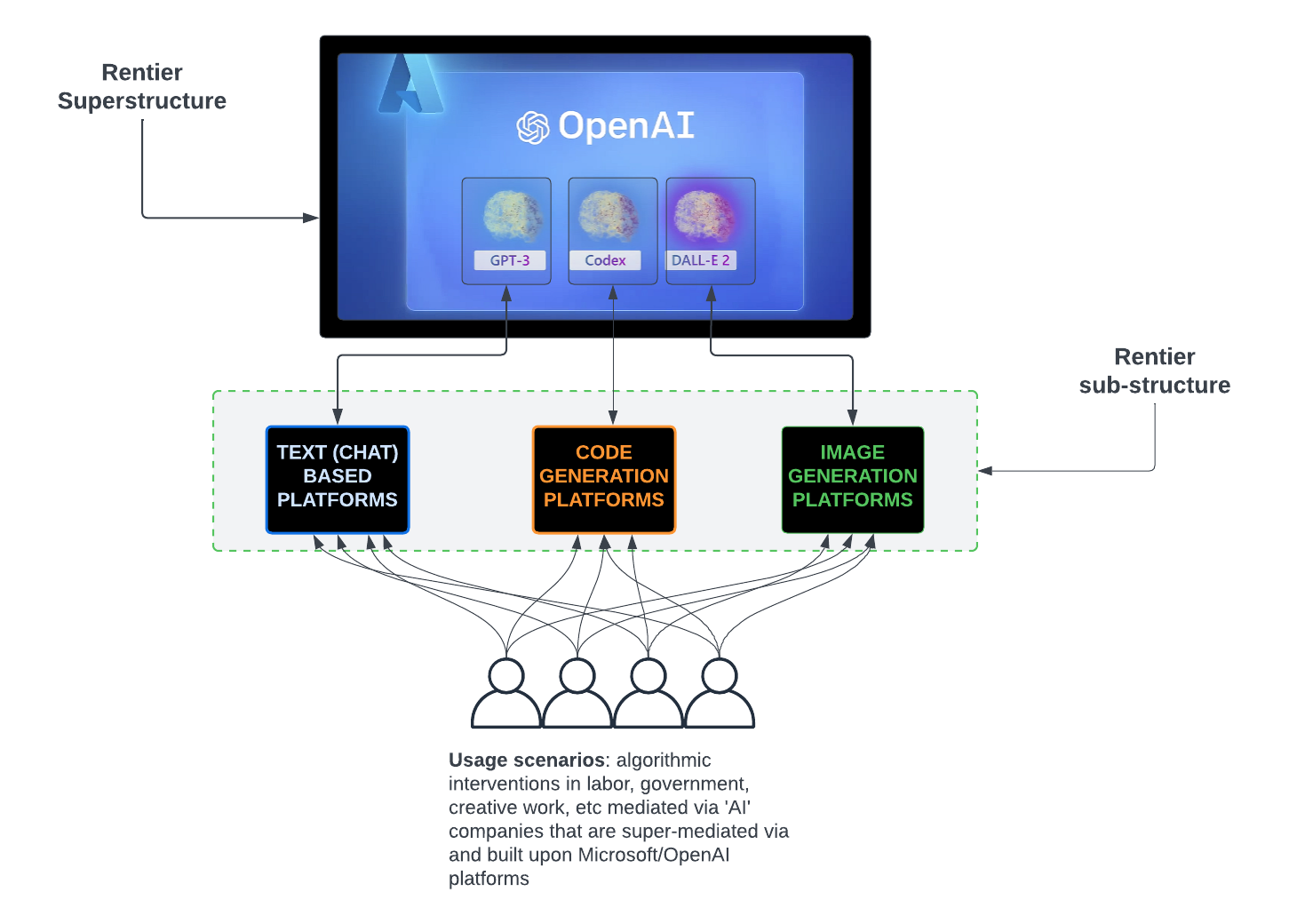

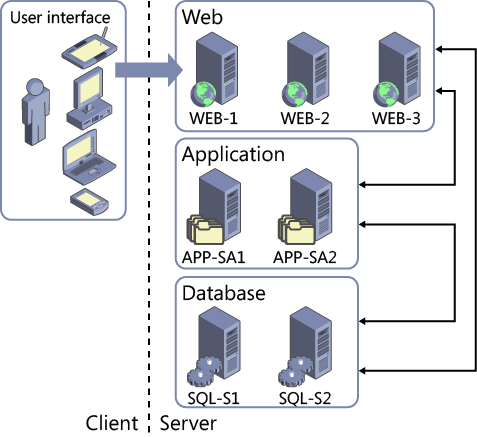

The SAGE system was built to create a method and infrastructure for gathering data from far flung sources and coordinating a response to what its numerous displays told people in Strategic Air Command facilities. This military purpose provided the foundation, metaphor and philosophy shaping the uses of systems that eventually came online such as commercial mainframe computers, client server architectures and what is known as ‘cloud computing.’

Note this image of SAGE system elements:

In design intent and philosophy, there is a link between the vision of computation as a means of commanding people and controlling events that shaped the SAGE system and corporate methods such as business intelligence described in this Wikipedia article:

“Business intelligence (BI) consists of strategies, methodologies, and technologies used by enterprises for data analysis and management of business information. Common functions of BI technologies include reporting, online analytical processing, analytics, dashboard development, data mining, process mining, complex event processing, business performance management, bench marking, text mining, predictive analytics, and prescriptive analytics.”

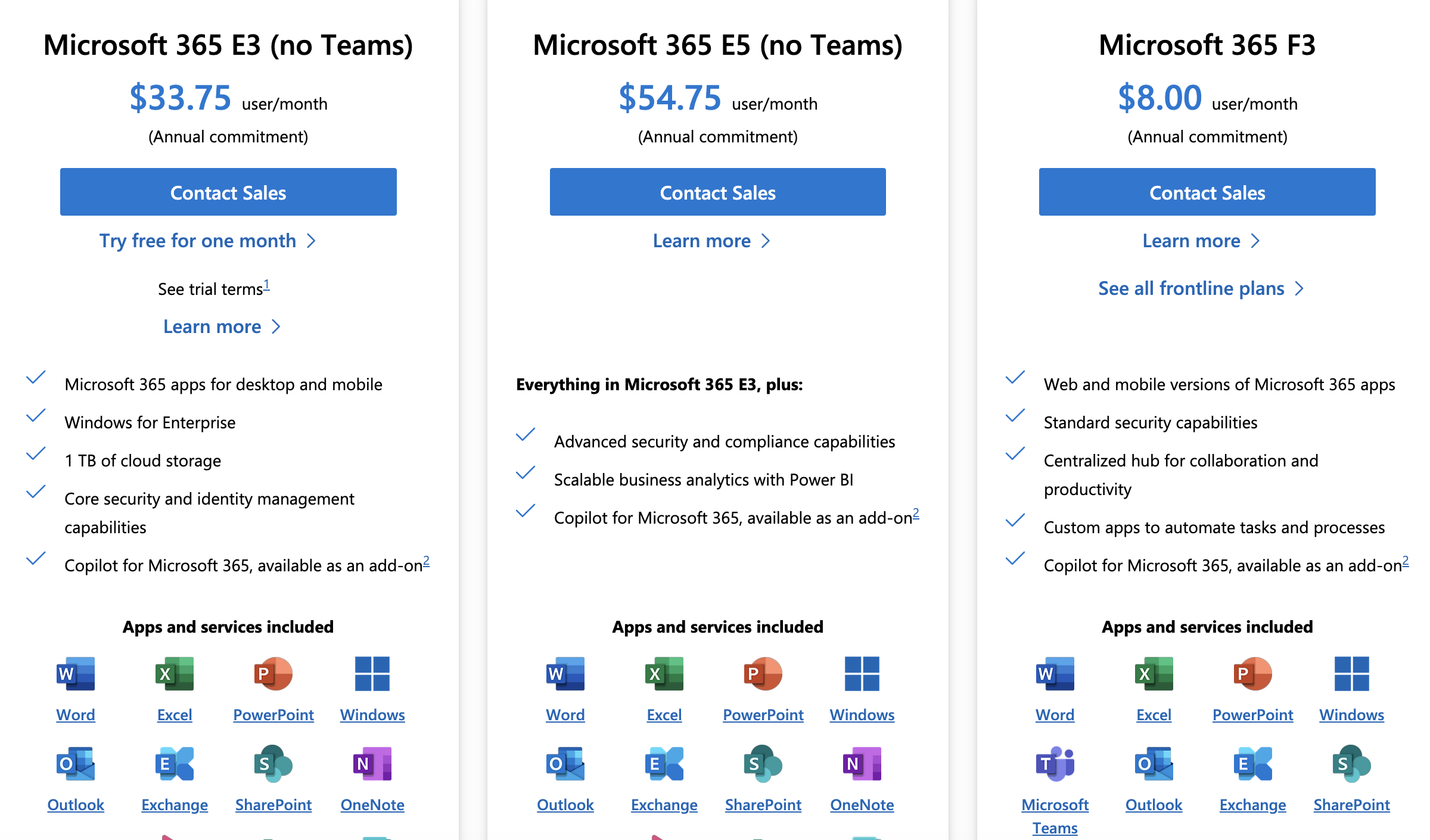

Microsoft, never one to miss an opportunity to simultaneously shape and profit from business requirements, real or imagined (does anyone recall the Metaverse? It disappeared, like youth, or money from your bank account) provides a visual of how a business intelligence platform can be built on their Azure platform:

The common goal – the thematic bridge from SAGE to business intelligence – is data gathering and analysis which, as an objective in abstract, is not at all sinister. Every society and every social organization, no matter how large or small, needs to understand its environment, collect information and act upon what is learned. Just as SAGE applied that methodology to the task of nuclear war (which, outside of the insane circles running the world to ruin, is no one’s idea of a good use case) corporations apply it to maximizing profit. In the capitalist world, we are data points to be ingested, analyzed and optimized via something called KPIs.

Key Performance Indicators – the SAGE of Corporate Life

Key Performance Indicators or, KPIs, are the metric used to include our behavior and actions as workers, into a command and control schema. What, in the past, was directed without the aid of software (Taylorism being the first, formalized example of a pre software method) is now measured as data points stored in databases and spreadsheets. How ‘productive’ are you? KPIs, we’re told, are a way to ensure workers are on track from the perspective of owners. In a 2021 article titled ‘Why You Need Personal KPIs To Achieve Your Goals’, Forbes, a magazine once treated as scripture, advised ‘professionals’ (a word used to lobotomise that portion of one’s mind that is aware of your status as a precarious worker) to use KPIs to shape their careers:

“Peter Drucker famously said that “what is measured is managed, and what is managed gets improved.” Key Performance Indicators (KPI) are a staple of every business. It is the tool used to measure how effectively an organization is meeting vital business objectives. Teams, departments, and organizations initiate the KPIs so that it spreads to every level of an institution. If it’s such a prominent accountability measure in the business sector, why not use it for our professional success? Perhaps we should inculcate personal KPIs into our practice.”

This is good advice in a way not unlike the sort of contextually useful counsel you’d get on how to handle yourself in a bar fight or dealing with a cop who’s obsessed with demonstrating his authority; you contort yourself to survive. It’s useful, but its utility is a sign of a problem, of a system of artificially enforced limits whose boundaries serve others’ interests.

…

In his 2018 book, ‘Surveillance Valley’, journalist Yasha Levine details the links between the US’ intelligence agencies and Silicon Valley. From the beginning, Levine shows, companies such as Oracle and technologies we think sprung into existence on the sun blasted terrain of California like dreams were nurtured and even created by the US’ surveillance apparatus.

There is a similar link between the techniques used by the corporations who dominate our lives and the systems and thinking which shaped the US’ command and control fixated response to the Cold War. Our work lives exist in the long shadow of the computers used to determine if ICBMs should wing their way to targets.