According to self-satisfied legend, medieval European scholars, perhaps short of things to do compared to we ever-occupied moderns, spent countless hours wondering about topics such as, how many angels could simultaneously occupy the head of a pin; the idea being that, if nothing was impossible for God, surely, violating the observable rules of space and temporality should be cosmic child’s play for the deity…but to what extent?

How many angels, oh lord?

Although it’s debatable whether this question actually kept any monks up at night more than, say, wondering where the best beer was, the core idea, that it’s possible to get lost in a maze of interesting, but ultimately pointless inquiries (a category which, in an ancient Buddhist text is labeled, ‘questions that tend not towards edification’) remains eternally relevant.

At this stage in our history, as we stare, dumbfounded, into the barrels of several weapons of capitalism’s making – climate change being the most devastating – the AI endeavor is the computational equivalent of that apocryphal medieval debating topic; we are discussing the ethics of large language models, focusing, understandably, on biased language and power consumption but missing a more pointed ethical question: should these systems exist at all? A more, shall we say, robust ethics would demand that in the face of our complex of global emergencies, tolerance for the use of computational power for games with language cannot be justified.

OPT-175B – A Lesson: Hardware

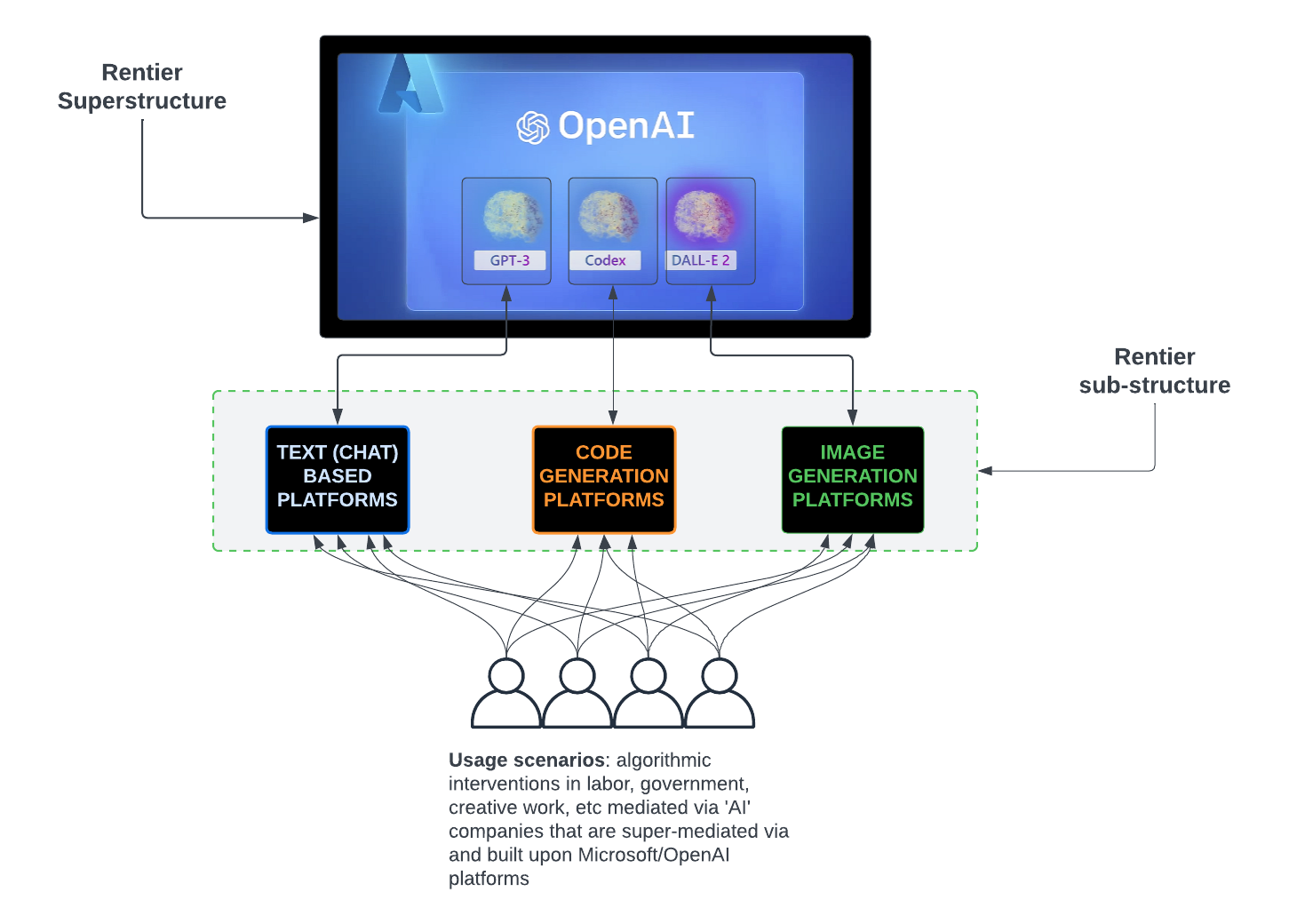

The company now known as Meta recently announced its creation of a large language model system called OPT-175B. Helpfully, and unlike the not particularly open OpenAI, the announcement was accompanied by the publication of a detailed technical review, which you can read here.

As the paper’s authors promise in the abstract, the document is quite rich in details which, to those unfamiliar with the industry’s terminology and jargon, will likely be off-putting. That’s okay because I read it for you and can distill the results to four main items:

- The system consumes almost a thousand NVIDIA game processing units (992 to be exact, not counting the units that had to be replaced because of failure)

- These processing units are quite powerful, which enabled the OPT-175B team to use relatively fewer computational resources than what was installed for GPT-3 another, famous (at least in AI circles) language model system

- OPT-175B, which drew its text data from online sources, such as that hive of villainy, Reddit, has a tendency to output racist and misogynist insults

- Sure, it uses fewer processors but its carbon footprint is still excessive (again, not counting replacements and supply chain)

Here’s an excerpt from the paper:

“From this implementation, and from using the latest generation of NVIDIA hardware, we are able to develop OPT-175B using only 1/7th the carbon footprint of GPT-3.

While this is a significant achievement, the energy cost of creating such a model is still nontrivial, and repeated efforts to replicate a model of this size will only amplify the growing compute footprint of these LLMs.” [highlighting emphasis mine]

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2205.01068.pdf

I cooked up a visual to place this in a fuller context:

Here’s a bit more from the paper about hardware:

“We faced a significant number of hardware failures in our compute cluster while training OPT-175B.

In total, hardware failures contributed to at least 35 manual restarts and the cycling of over 100 hosts over the course of 2 months.

During manual restarts, the training run was paused, and a series of diagnostics tests were conducted to detect problematic nodes.

Flagged nodes were then cordoned off and training was resumed from the last saved checkpoint.

Given the difference between the number of hosts cycled out and the number of manual restarts, we estimate 70+ automatic restarts due to hardware failures.”

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2205.01068.pdf

All of which means that, while processing data, there were times, quite a few times, when parts of the system failed, requiring a pause till fixed or routed around (resumed, once the failing elements were replaced).

Let’s pause here to reflect on where we are in the story; a system, whose purpose is to produce plausible strings of text (and, stripped of the obscurants of mathematics, large-scale systems engineering and marketing hype, this is what large language models do) was assembled using a small mountain of computer processors, prone, to a non-trivial extent, to failure.

As pin carrying capacity counting goes, this is rather expensive.

OPT-175B – A Lesson: Bias

Like other LLMs, OPT-175B has a tendency to return hate speech as output. Another excerpt:

“Overall, we see that OPT-175B has a higher toxicity rate than either PaLM or Davinci. We also observe that all 3 models have increased likelihood of generating toxic continuations as the toxicity of the prompt increases, which is consistent with the observations of Chowdhery et al. (2022). As with our experiments in hate speech detection, we suspect the inclusion of unmoderated social media texts in the pre-training corpus raises model familiarity with, and therefore propensity to generate and detect, toxic text.” [bold emphasis mine]

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2205.01068.pdf

Unsurprisingly, there’s been a lot of commentary on Twitter (and no doubt, elsewhere) about this toxicity. Indeed, almost the entire focus of ‘ethical’ efforts has been on somehow engineering this tendency away – or perhaps avoiding it altogether via the use of less volatile datasets (and good luck with that as long as Internet data is in the mix!)

This defines ethics as being the task of improving a system’s outputs – a technical activity – and not a consideration of a system as a whole from an ethical standpoint within political economy. Or to put it another way, the ethical task is narrowed to making sure that if I use a service which, on its backend, depends on a language model for its apparent text capability, it won’t in the midst of telling me about good nearby restaurants, hurl insults like a klan member.

OPT-175B – A Lesson: Carbon

Within the paper itself, there is the foundation of an argument against this entire field, as currently pursued:

“...there exists significant compute and carbon cost to reproduce models of this size. While OPT-175B was developed with an estimated carbon emissions footprint (CO2eq) of 75 tons,10 GPT-3 was estimated to use 500 tons, while Gopher required 380 tons. These estimates are not universally reported, and the accounting methodologies for these calculations are also not standardized. In addition, model training is only one component of the over- all carbon footprint of AI systems; we must also consider experimentation and eventual downstream inference cost, all of which contribute to the growing energy footprint of creating large-scale models.”

A More Urgent Form of Ethics

In the fictional history of the far-future world depicted in the novel ‘Dune’ there was an event, the Butlerian Jihad, which decisively swept thinking machines from galactic civilization. This purge was inspired by the interpretation of devices that mimicked thought or possessed the capacity to think as an abomination against nature.

Today, we do not face the challenge of thinking machines and probably never will. What we do face however, is an urgent need to, at long last, take climate change seriously. How should this reorientation towards soberness alter our understanding of the role of computation?

I think that, in face of an ever-shortening amount of time to address climate change in an organized fashion, the continuation, to say nothing of expansion of this industrial level consumption of resources, computing power, talent and the corresponding carbon footprint is ethically and morally unacceptable.

At this late hour, the ethical position isn’t to call for, or work towards better use of these massive systems; it’s to demand they be halted and the computational capacity re-purposed for more pressing issues. We can no longer afford to wonder how many angels we can get to dance on pins.