I’m writing this quickly, as if it’s a dispatch from the front because ideas – and memories – are flowing rather freely and I want to get it all down while synapses are hot.

A bit of establishing preamble…

This post is inspired by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank – today’s topic for social media’s legion of instant experts to opine about – but it’s not directly about that event. It is, however, about a situation, at the beginning of my career in computation, when I was working at a bank which the FDIC took command of because things had gotten completely out of hand in the most ridiculous way.

When I graduated from college, I faced a problem common for young people: how to find a job that didn’t completely suck and which, somehow, even tangentially, justified the loan(s) which drifted above one’s head like all the swords Dionysis could marshall to terrorize a sweating Damocles. My friends, I failed at finding such a job but, with the help of a friend I did find a job: working in the reconciliation department of a boutique bank.

In those days, long before Teslas exploded on the US’ poorly maintained roads, burning with the heat of tactical nukes, reconciliation was done by people, staring at printouts, tasked with ensuring the deposits and withdrawals from accounts were properly balanced. At this point, being clever, you’re no doubt staring in disbelief at your screen, perhaps shouting: but isn’t that just the thing for computers?!

Yes, yes it is but this particular bank, in the 1990s, had yet to make the investment in the systems required to perform this work via automation. And so, there I was, staring at printouts, and often making mistakes. I’m not ashamed to tell you that charm alone kept me in that job.

Until…

One day, during a routine bank audit, a government representative, observing my struggles to keep my eyes open, asked ‘do you do manual reconciliations here?’ Reader, I was young and did not possess all the corporate political savvy I acquired over time in years to come and so, answering honestly, I smiled and said: yes!

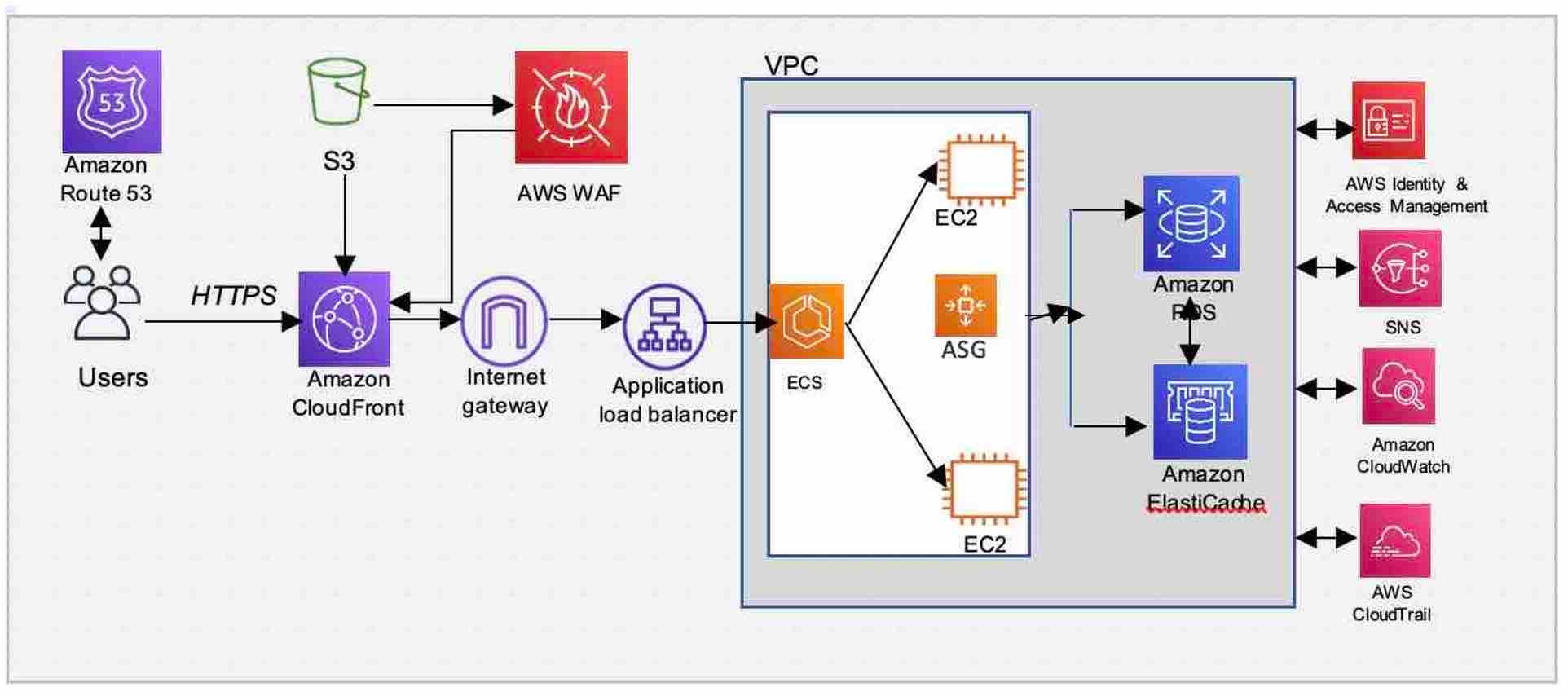

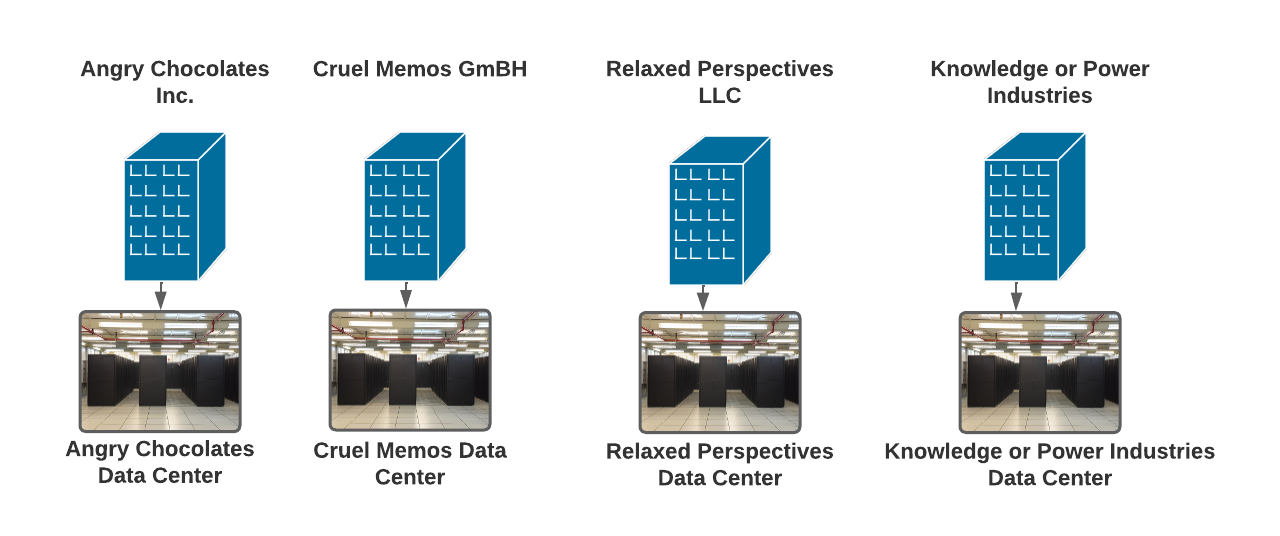

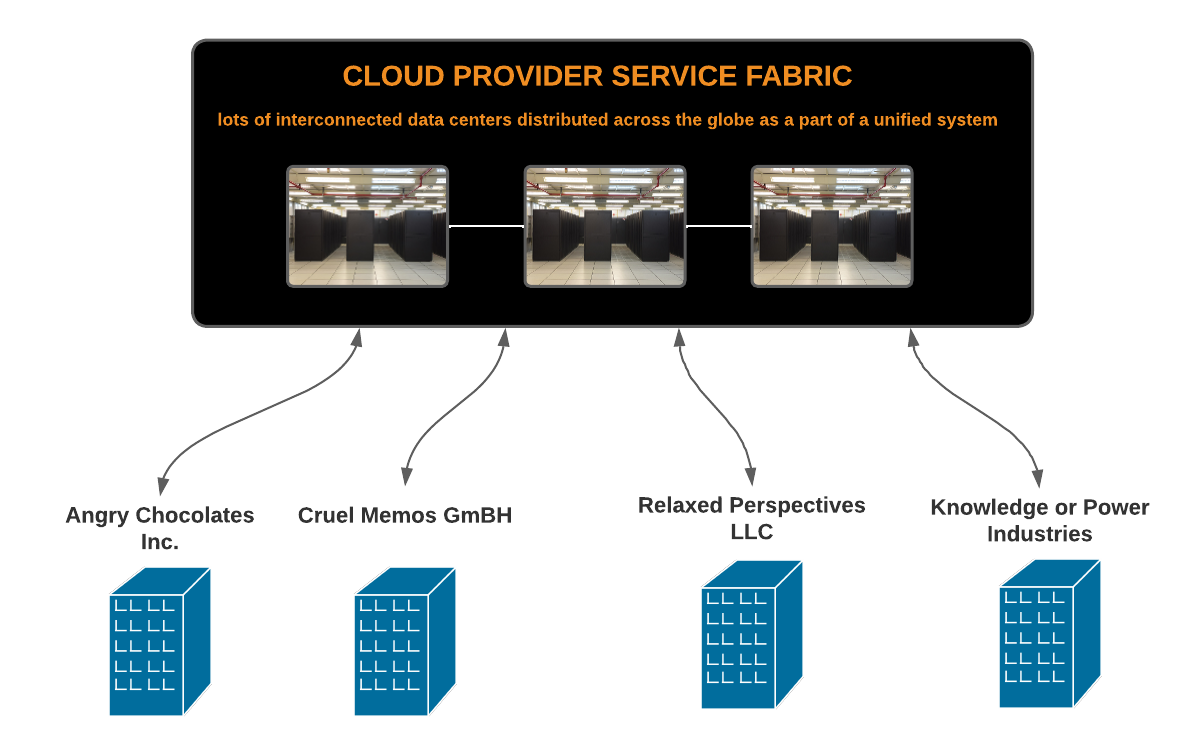

Ah ha! This caused a cascade of events. The audit’s scope expanded to include a more thorough review of the bank’s technology usage. Not only was the bank using inept (but charming!) college graduates to reconcile accounts, all account data was stored off site with an Atlanta based company named FISERV. The terminals tellers used were linked via devices called CSU/DSU modems to mainframes and servers hosted and owned by FISERV. So, when you, in those pre exploding Tesla days, walked into the bank (as people did) to request your balance or make a deposit, the teller interacted, via their greenscreen terminal and through the CSU/DSU with computers many miles away.

Typically, this worked well enough but because the gods are capricious, it just so happened that an outage occurred during a time auditors were on site. Deposits, withdrawals and balance inquiries were made but the data had to be temporarily stored on bank branch devices before being transmitted to FISERV once the connection was restored.

An auditor noticed a stream of customers being told about the outage and this made its way into her findings.

And it was those findings that launched my career because, one of the recommendations (more a command than a suggestion) was that the bank use a client/server computational system to have local processing rather than simple terminals and data far, far away.

But who would put this command into action?

A bank vice president, nice enough as VPs go, walked over to my reconciliation cube, filled with printouts and despair, put his hand on my shoulder (this is not an exaggeration) and said, ‘come with me.’ This wasn’t totally random. I’d had conversations with this very VP about the need to modernize the bank’s computational infrastructure and had made the exact same suggestion because I was a computer nerd by both inclination and formal training.

So, to him, I was a natural fit for a new role: Systems Administrator.

I won’t bore you with a recounting of all the work (the late nights, budget meetings, technical challenges and vendor negotiations) that went into creating the system the bank eventually used, which I architected and oversaw because the real point of this hurriedly written essay is bank collapse.

Now let’s talk about the effects of having better data, locally stored because, lovely reader, during the following year’s audit, using the readily available data stored on bank servers – the very servers I lovingly brought online and configured – the FDIC was able to find something very odd indeed.

Some of the loans that formed the bank’s portfolio were not ‘performing’ as the term goes. That is, these particular loans had been issued to customers (the founder’s circle of friends) but few, and in some cases, no payments were made against them. There also seemed to be two sets of loan portfolios – one showing the true state and the other, well, not so true.

The same auditor who, the year before, had called for better computation was now approaching me to produce report after report for deeper analysis. Suddenly, I was receiving phone calls from board members inquiring about what the feds were asking for. One flashy board member offered to take me out to dinner at a Michelin starred restaurant and help me up my suit game. All because, at that moment, I was the primary conduit for detailed technical information to a powerful government agency. There was an effort to, shall we say, influence the data shared. I was young, valued reader, but not that young; those efforts failed.

It was crazy in those streets and by ‘streets’ I mean the offices of this apparently shady bank.

Oh, what a time that was… a fired bank founder and President, the bank in receivership, a new board, a VP for loans trying to explain herself, more money for computation, an ill advised office romance. It was all there, on the 50th floor.

So when I think of SVB, among other, more contemporary thoughts, I recall that moment, in another age and wonder what sleepless nights are vexing the technical staff of SVB.