In part one of this series, I proposed that Trump’s second term, which, as we’re seeing with the rush of executive orders, has, unlike his first, a coherent agenda (centered on the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 plan), would be a time of increased aggression against ostracized individuals and groups, a state of exception in which the pretence of bourgeois democracy melts away.

Because of this, we should change our relationship with the technologies we’re compelled to use; a naive belief in the good will or benign neglect of tech corporations and the state should be abandoned. The correct perspective is to assume breach.

In a April, 2023 published blog post for the network equipment company, F5, systems security expert Ken Arora, described the concept of assume breach:

Plumbers, electricians, and other professionals who operate in the physical world have long internalized the true essence of “assume breach.” Because they are tasked with creating solutions that must be robust in tangible environments, they implicitly accept and incorporate the simple fact that failures occur within the scope of their work. They also understand that failures are not an indictment of their skills, nor a reason to forgo their services. Rather, it is only the most skilled who, understanding that their creations will eventually fail, incorporate learnings from past failures and are able to anticipate likely future failures.

[…]

For the purposes of this essay, the term, failure, is re-interpreted to mean the intrusion of hostile entities into the systems and devices you use. By adopting a technology praxis based on assumed breach, you can plan for intrusion by acknowledging the possibility that your systems have, or will be penetrated.

Primarily, there are five areas of concern:

- Phones

- Social Media

- Personal computers

- Workplace platforms, such as Microsoft 365 and Google’s G-Suite

- ‘Cloud’ platforms, such as Microsoft Azure, Amazon AWS and Google Cloud Platform

It’s reasonable to think that following security best practices for each technology (links in the references section) offers a degree of protection from intrusion. Although this may be true to some extent, when contending with non-state hostiles, such as black hat hackers, state entities have direct access to the ownership of these systems, giving them the ability to circumvent standard security measures via the exercise of political power.

Phones (and tablets)

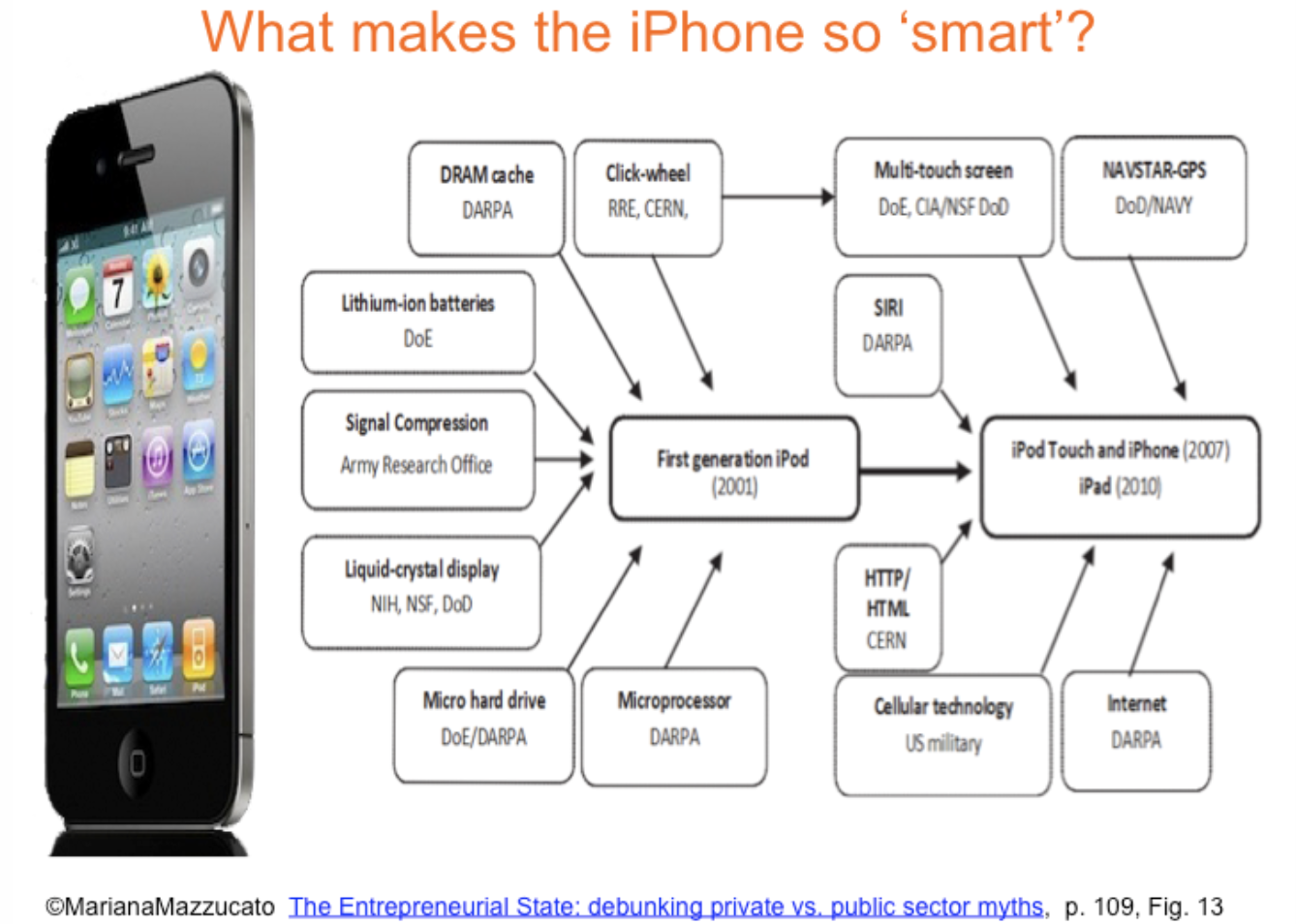

Phones are surveillance devices. No communications that require security and which, if intercepted, could lead to state harassment or worse should be done via phones. This applies to iPhones, Android phones and even niche devices such as Linux phones. Phones are a threat in two ways:

- Location tracking – phones connect to cellular networks and utilize unique identifiers that enable location and geospatial tracking. This data is used to create maps of activity and associations (a technique the IDF has used in its genocidal wars)

- Data seizure – phones store data that, if seized by hostiles, can be used against you and your organization. Social media account data, notes, contacts and other information

Phone use must be avoided for secure communications. If you must use a phone for your activist work, consider adopting a secure Linux-based phone such as GrapheneOS which may be more resistant to cracking if seized but not to communication interception. As an alternative, consider using old school methods, such as paper messages conveyed via trusted courier within your group. This sounds extreme and may turn out to be unnecessary depending on how conditions mutate. It is best however, to be prepared should it become necessary.

Social Media

Social media platforms such as Twitter/X, Bluesky, Mastodon, Facebook/Meta and even less public systems such as Discord, which enables the creation of privately managed servers, should not be used for secure communication. Not only because of posts, but because direct messages are vulnerable to surveillance and can be used to obtain pattern and association data. A comparatively secure (though not foolproof) alternative is the use of the Signal messaging platform. (Scratch that: Yasha Levine provides a full explantation of Signal as a government op here).

Personal Computers

Like phones, personal computers -laptops and Desktops – should not be considered secure. There are several sub-categories of vulnerability:

- Vulnerabilities caused by security flaws in the operating system (for example, issues with Microsoft Windows or Apple MacOS)

- Vulnerabilities designed into the operating systems by the companies developing, deploying and selling them for profit objectives (Windows CoPilot, is a known threat vector, for example)

- Vulnerabilities exploited by state actors such as intelligence and law enforcement agencies (deliberate backdoors)

- Data exposure if a computer is seized

Operating systems are the main threat vector – that is, opening to your data – when using a computer. In part one of this series, I suggested abandoning the use of Microsoft Windows, Google Chrome OS and Apple’s Mac OS for computer usage that requires security and using secure Debian Linux instead. This is covered in detail in part one.

Workplace Platforms such as Google G-Suite and Microsoft 365 and other ‘cloud’ platforms such Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services

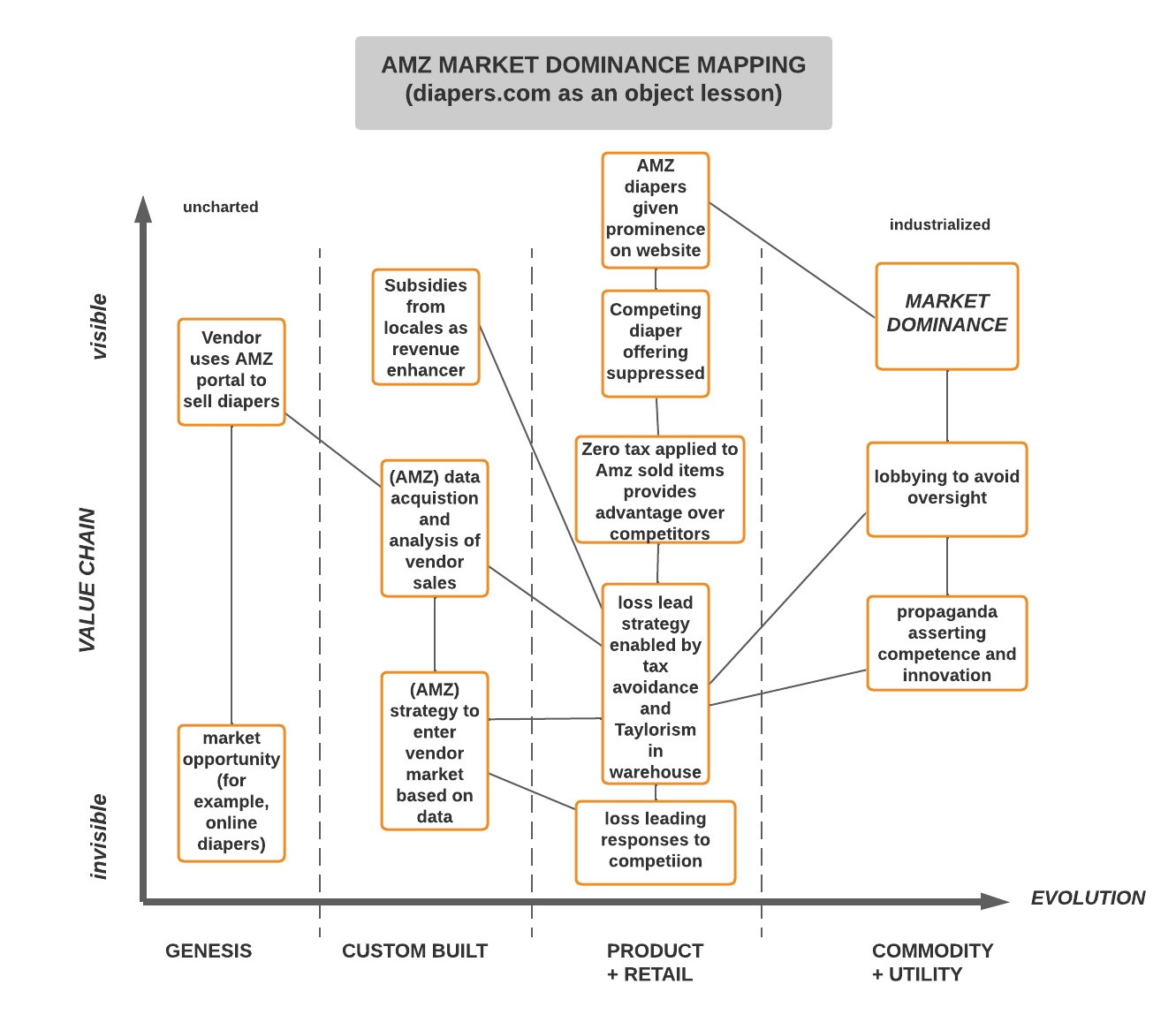

Although convenient, and, in the case of Software as a Service offerings such as Google G-Suite and Microsoft 365, less technically demanding to manage than on-premises hosting, ‘cloud’ platforms should not be considered trustworthy for secure data storage or communications.

This is true, even when platform-specific security best practices are followed because such measures will be circumvented by the corporations that own these platforms when it suits their purposes – such as cooperating with state mandates to release customer data.

The challenge for organizations who’re concerned about state sanctioned breach is finding the equipment, technical talent, will and organizational skill (project management) to move away from these ‘cloud’ systems to on-premises platforms. This is not trivial and has so many complexities that it deserves a separate essay, which will be part three of this series.

The primary challenges are:

- Inventorying the applications you use

- Assessing where the organisation’s data is stored and the types of data

- Assessing the types of communications and the levels of vulnerability (for example, how is email used? What about collaboration services such as SharePoint?)

- Crafting an achievable strategy for moving applications, services and data off the vulnerable cloud service

- Encrypting and deleting data

…

In part three of this series, I will describe moving your organisation’s data and applications off of cloud platforms: what are the challenges? What are the methods? What skills are required? I’ll talk about this and more.

References

Security Best Practices – Google Workspace

Microsoft 365 Security Best Practices

Questions and Answers: Israeli Military’s Use of Digital Tools in Gaza

UK police raid home, seize devices of EI’s Asa Winstanley

Meta-provided Facebook chats led a woman to plead guilty to abortion-related charges