[In this post, Monroe thinks aloud about his approach to analyzing the tech industry, a term which, annoyingly, is almost exclusively used to describe Silicon Valley based companies that use software to create rentier platforms and not, say, aerospace and materials science firms. The key concept is materialism.]

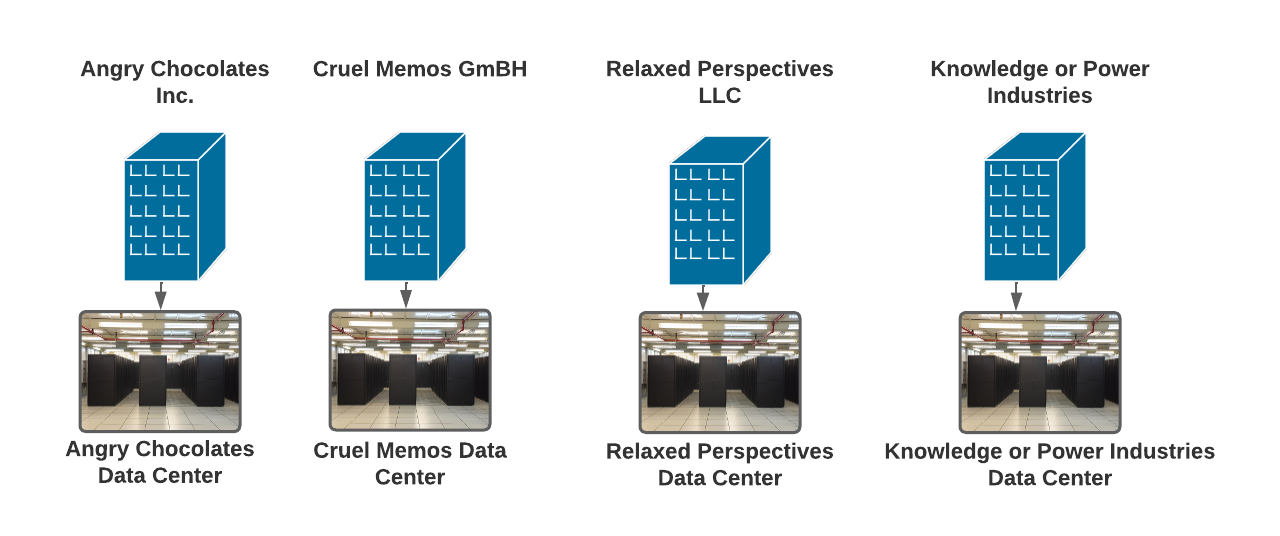

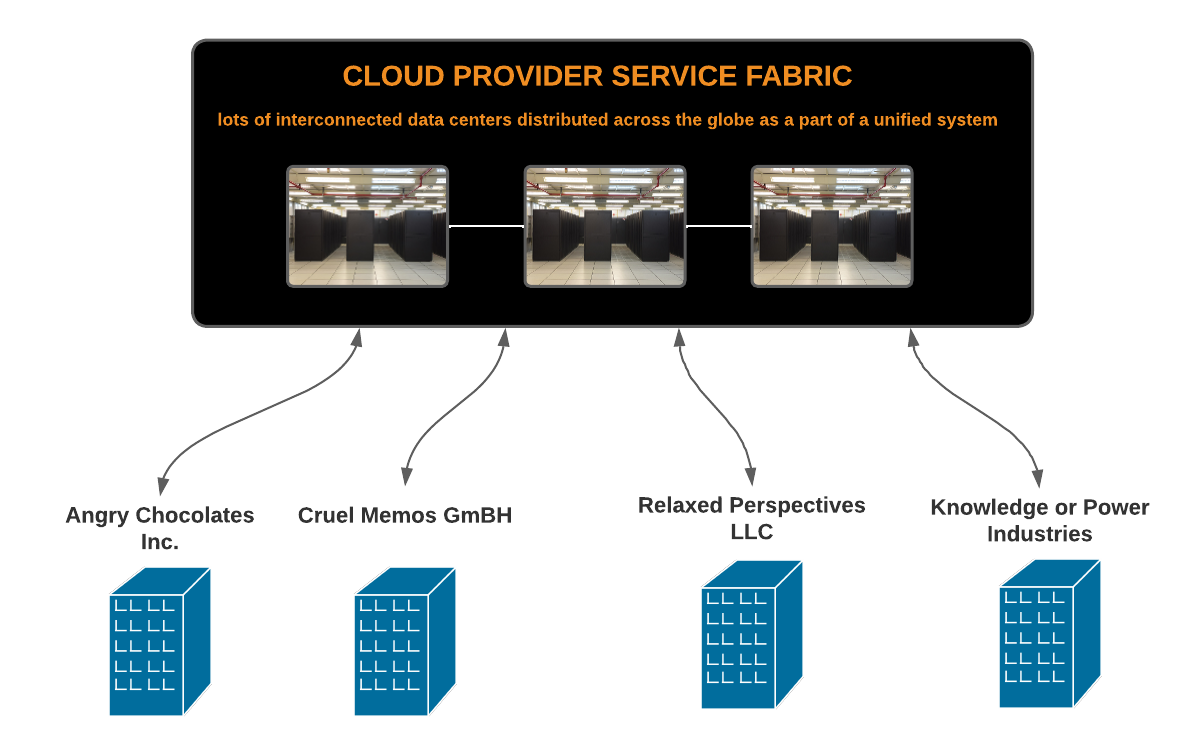

Few industries are as shrouded by mystification as the tech sector, defined as that segment of the industrial and economic system whose wealth and power have been built by acting as the unavoidable foundation of all other activity, by building rentier software-based platforms, shielded by copyright, that are difficult, indeed, impossible, to circumvent (an early example is the method Microsoft used to extract, via its monopoly position in corporate desktop software, what was called the ‘Microsoft or Windows tax‘).

Consider, as a contrasting example, a paper clip company: if it was named something self-consciously clever, such as Phase Metallics, it wouldn’t take long for most of us to see through this vainglory to say: ‘calm down, you make paper clips’.

An instinctual grounding of opinion, shaped and informed by the irrefutable physicality of things like paper clips, is lacking when we assess the claims of ‘tech’ companies. The reason is because the industry has successfully obscured, with a great deal of help from the tech press and media generally, the material basis of its activities. We use computers but do not see the supply chains that enable their production as machines. We use software but are encouraged to view software developers (or ‘engineers’, or ‘coders’) as akin to wizards and not people creating instruction sets.

Computers and software development are complex artifacts and tasks but not more complex than physics or civil engineering. We admire the architects, engineers and construction workers who design and build towering structures but, even though most of us don’t understand the details, we know these achievements have a physical, material basis and face limitations imposed by nature and our ability to work within natural constraints.

The tech sector presents itself as being outside of these limitations and most people, intimidated by insider jargon, the glamour of wealth and the twin delusions of techno-determinism (which posits a technological development as inevitable) and techno-optimism (which asserts there’s no limit to what can be achieved) are unable to effectively counter the dominant narrative.

The tech industry effectively deploys a degraded form of Platonic idealism (which places greater emphasis on our ideas of the world than the actually existing structure of the world itself). This idealism prevents us from thinking clearly about the industry’s activities and its role in, and impact on, global political economy (the interrelation of economic activity with social custom, legal frameworks, government, and power relations). One of the consequences of this idealist preoccupation is that, when we’re analyzing a press account of tech activities, for example, stories about autonomous cars, instead of interrogating the assumption that driverless vehicles are possible and inevitable, we base our analysis on an idealist claim, thereby going astray and inadvertently allowing our class adversaries to define the boundaries of discussion.

The answer to this idealism, and the propaganda crafted using it, is a materialist approach to tech industry analysis.

Materialism (also known as physicalism)

Let’s take a quote from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Physicalism is, in slogan form, the thesis that everything is physical. The thesis is usually intended as a metaphysical thesis, parallel to the thesis attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Thales, that everything is water, or the idealism of the 18th Century philosopher Berkeley, that everything is mental. The general idea is that the nature of the actual world (i.e. the universe and everything in it) conforms to a certain condition, the condition of being physical. Of course, physicalists don’t deny that the world might contain many items that at first glance don’t seem physical — items of a biological, or psychological, or moral, or social, or mathematical nature. But they insist nevertheless that at the end of the day such items are physical, or at least bear an important relation to the physical.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/physicalism/

This blog is dedicated to ruthlessly rejecting tech industry idealism in favor of tracking the hard physicality and real-world impacts of computation in all of its flavors. In this sense, the focus is materialist. Key concerns include:

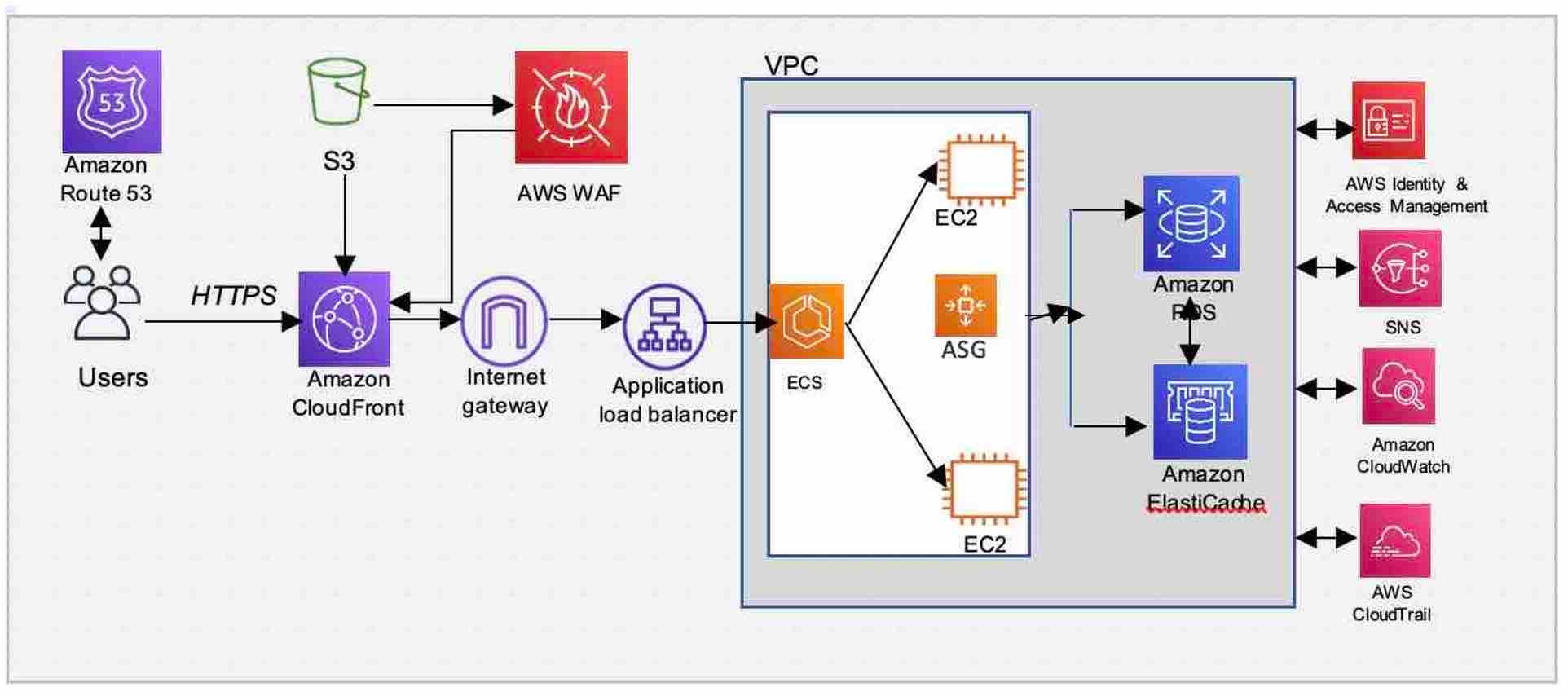

- Investigating the functional, computational foundation of platforms, such as Apple’s walled garden and Facebook

- Exploring the physical inputs into the computational layer and the associated costs (in ecological, political economy and societal impact terms)

- Asking who, and what factors shape the creation and deployment of software at-scale – i.e., what is the relationship between software and power

This blog’s analytical foundation is unequivocally Marxist and seeks to employ Marx and Engel’s grounding of Hegelian dialectics (an ongoing project, subject to endless refinement as understanding improves):

Marx’s criticism of Hegel asserts that Hegel’s dialectics go astray by dealing with ideas, with the human mind. Hegel’s dialectic, Marx says, inappropriately concerns “the process of the human brain”; it focuses on ideas. Hegel’s thought is in fact sometimes called dialectical idealism, and Hegel himself is counted among a number of other philosophers known as the German idealists. Marx, on the contrary, believed that dialectics should deal not with the mental world of ideas but with “the material world”, the world of production and other economic activity.[19] For Marx, a contradiction can be solved by a desperate struggle to change the social world. This was a very important transformation because it allowed him to move dialectics out of the contextual subject of philosophy and into the study of social relations based on the material world.

Wikipedia “Dialectical Materialism” – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialectical_materialism

This blog is, therefore, dedicated to finding ways to apply the Marx/Engels conceptualization of materialism to the tech industry.

Conclusion

When I started my technology career, almost 20 years ago, like most of my colleagues, I was an excited idealist (in both the gee whiz and philosophical senses of the term) who viewed this burgeoning industry as breaking old power structures and creating newer, freer relationships (many of us, for example, really thought Linux was going to shatter corporate power just as some today think ‘AI’ is a liberatory research program).

This was an understandable delusion, the result of youthful enthusiasm but also, the hegemonic ideas of that time. These ideas – of freedom, ‘innovation’ and creativity are still deployed today but like crumbling Roman ruins, are only a shadow of their former glory.

The loss of dreams can lead to despair, but, to paraphrase Einstein, if we look deeply into the structures of things as they are, instead of as we want them to be, instead of despair, we can feel a new type of invigoration, the falling away of childlike notions and a proper identification of enemies and friends.

A materialist approach to the tech industry removes the blinders from one’s eyes and reveals the full landscape.